A/B Testing Fundamentals

If you are new to A/B testing, you may find a lot of new terminology. The goal of this section is to help you understand the basics of A/B testing.

Glossary - Common Experimentation Terms

Control (or Baseline)

The existing version of the product that you are trying to improve upon.

Variation (or Treatment)

A new version of the page that you are testing against the Control.

Hypothesis

Formal way to describe what you are changing and what you think it will do.

Statistical Significance

An indicator that the difference in performance between the control and treatment groups is unlikely to have occurred by chance.

Confidence level

The level of certainty we want before the result of a test is statistically significant. A common confidence level used in A/B testing is 95%.

Sample size

The number of visitors or users who are included in the A/B test.

Test duration

The length of time that the A/B test is run. This can vary depending on the sample size and the desired confidence level.

Variance

The degree to which the results of an A/B test vary over time or across different segments of the user base.

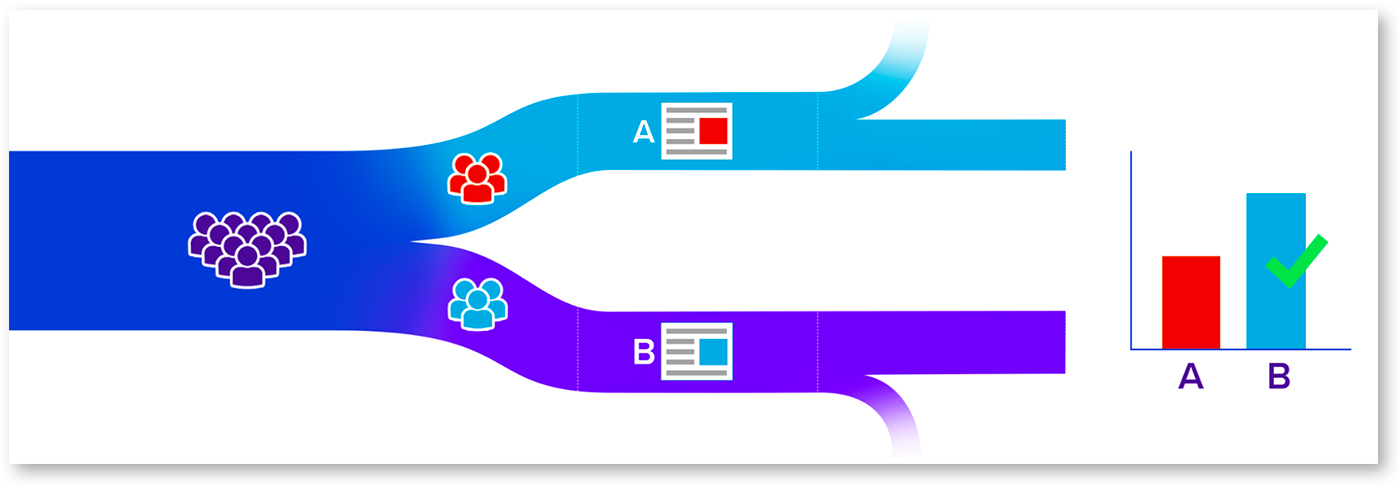

Anatomy of an A/B test

Hypothesis Come up with an idea you want to test | Assignment Randomly split your audience into persistent groups | Variations Create and show different experiences to each group | Tracking Record events and behaviors of the two groups | Results Use statistics to determine if the differences in behavior are significant |

Hypothesis

Good A/B tests, and really any project, starts with a hypothesis about what you’re trying to do. A good hypothesis should be as simple, specific, and falsifiable as possible.

A good A/B test hypothesis should be:

- Specific: The hypothesis should clearly state what you want to test and what outcome you expect to see.

- Measurable: The hypothesis should include a metric or metrics that can be used to evaluate the outcome of the test.

- Relevant: The hypothesis should be relevant to your business goals and objectives.

- Clear: The hypothesis should be easy to understand and communicate to others.

- Simple: The fewer variables that are involved in the experiment, the more causality can be implied in the results.

- Falsifiable: The hypothesis should be something that can be tested using an A/B test to determine the validity of the hypothesis.

Overall, a good A/B test hypothesis should be a clear statement that identifies a specific change you want to make and the expected impact on a measurable outcome, while being grounded in data and relevant to your business goals.

Audience and Assignments

Choose the audience for your experiment. To increase the detectable effect of your experiment, the audience you choose should be as close to the experiment as possible. For example, if you’re focusing on a new user registration form, you should select as your audience just unregistered users. If you were to include all users, you would have users who could not see the experiment, which would increase the noise and reduce the ability to detect an effect. Once you have selected your audience, you will randomize users to one variation or another.

Variations

An A/B test can include as many variations as you like. Typically the A variation is the control variation. The variations can have as many changes as you like, but the more you change the less certain you can be what caused the change.

Tracking

Tracking is the process of recording events and behaviors that your users do. In the context of AB testing, you want to track events that happen after exposure to the experiment, as these events will be used to determine if there is a change in performance due to being exposed to the experiment. AB testing systems either are "warehouse native" (like GrowthBook) as in they use your existing event trackers (like GA, Segment, Rudderstack, etc), or they require you to send event data to them.

Results

With A/B testing we use statistics to determine if the effect we measure on a metric of interest is significantly different across variations. The results of an A/B test on a particular metric can have three possible outcomes: win, loss, or inconclusive. With GrowthBook we offer two different statistical approaches, Frequentist and Bayesian. By default, GrowthBook uses Bayesian statistics. Each method has their pros and cons, but both will provide you with evidence as to how each variation affected your metrics.

Experimentation Basics

Typical success rates

A/B testing can be incredibly humbling—one quickly learns how often our intuition about what will be successful with our users is incorrect. Industry wide average success rates are only about 33%. ⅓ of the time our experiments are successful in improving the metrics we intended to improve, ⅓ of the time we have no effect, and ⅓ of the time we hurt those metrics. Furthermore, the more optimized your product is, the lower your success rates tend to be.

But A/B testing is not only humbling, it can dramatically improve decision making. Rather than thinking we only win 33% of the time, the above statistics really show that A/B tests help us make a clearly right decision about 66% of the time. Of course, shipping a product that won (33% of the time) is a win, but so is not shipping a product that lost (another 33% of the time). Failing fast through experimentation is success in terms of loss avoidance, as you are not shipping products that are hurting your metrics of interest.

Experiment power

With A/B testing, power analysis refers to whether a test can reliably detect an effect. Specifically, it is often written as the percent of the time a test would detect an effect of a given size with a given number of users. You can also think of the power of a test with respect to the sample size. For example: "How many times do I need to toss a coin to conclude it is rigged by a certain amount?"

Minimal Detectable Effect (MDE)

Minimal Detectable Effect is the minimum difference in performance between the control and treatment groups that can be detected by the A/B test, given a certain statistical significance threshold and power. The MDE is an important consideration when designing an A/B test because if the expected effect size is smaller than the MDE, then the test may not be able to detect a significant difference between the groups, even if one exists. Therefore, it is useful to calculate the MDE based on the desired level of statistical significance, power, and sample size, and ensure that the expected effect size is larger than the MDE in order to ensure that the A/B test is able to accurately detect the difference between the control and treatment groups.

False Positives (Type I Errors) and False Negatives (Type II Errors)

When making decisions about an experiment, we can say that we made the right decision when choosing to ship a winning variation or shut down a losing variation. However, because there is always uncertainty in the world and we rely on statistics, sometimes we make mistakes. Generally, there are two kinds of errors we can make: Type I and Type II errors.

Type I Errors: also known as False Positives, these are errors we make when we think the experiment provides us with a clear winner or a clear loser, but in reality the data are not clear enough to make this decision. For example, your metrics all appear to be winners, but in reality the experiment has no effect.

Type II Errors: also known as False Negatives, these are errors we make when the data appear inconclusive, but in reality there is a winner or a loser. For example, you run an experiment for as long as you planned to, and the data aren’t showing a clear winner or loser when actually a variation is much better or worse. Type II errors often require you to collect more data or choose blindly rather than provide you with the correct, clear answer

| Actual Results | ||||

| Inconclusive | Lost | Won | ||

| Decision Made | Inconclusive | Correct Inference | Type II error (false negative) | Type II error (false negative) |

| Shut down | Type I error (false positive) | Correct Inference | Type I error (false positive) | |

| Ship | Type I error (false positive) | Type I error (false positive) | Correct Inference | |

P-Value

In frequentist statistics, a p-value is a measure of the evidence against a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the hypothesis that there is no significant difference between two groups, or no relationship between two variables. In the context of A/B testing, the p-value is a statistical measure that indicates whether there is a significant difference between two groups, A and B.

The p-value is the probability of observing a difference as extreme or more extreme as your actual difference, given there is actually no difference between groups. If the p-value is less than a predetermined level of significance (often 0.05), the result is deemed to be statistically significant as the difference is not likely due to chance.

For example, let's say that you conduct an A/B test in which you randomly assign users to either group A (the control group) or group B (the experimental group). You measure a specific metric such as conversion rate for each group, and you calculate the p-value to test the hypothesis that there is no difference between the two groups. If the p-value is less than 0.05, the observed difference conversion rate between the two groups is unlikely if there wasn't truly a difference in groups; we say the effect is statistically significant and likely not due to chance.

It's important to note that p-value alone cannot determine the importance or practical significance of the findings. Additionally, it's essential to consider other factors such as effect size, sample size, and study design when interpreting the results.

A/A Tests

A/A testing is a form of A/B testing in which instead of serving two different variations, two identical versions of a product or design are tested against each other. In A/A testing, the purpose is not to compare the performance of the two versions, but rather to check the consistency of the testing platform and methodology.

The idea behind A/A testing is that if the two identical versions of the product or design produce significantly different results, then there may be an issue with the testing platform or methodology that is causing the inconsistency. By running an A/A test, you can identify and address any potential issues before running an A/B test, which can help ensure that the results of the A/B test are reliable and meaningful.

A/A testing is a useful tool for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of A/B tests, and can help improve the trust in the platform, and faith in the quality of the insights and decisions that are based on the results of these tests.

Read more about running A/A tests in GrowthBook.

Interaction effects

When you run multiple tests simultaneously, there's a chance they may interfere with each other. For example, two tests that change prices in different parts of your product could cause some users to see conflicting prices, eroding trust.

That's an extreme case. A more common scenario is when someone sees one experiment on the account registration page and another on the checkout page. If the tests run in parallel, users will see all combinations of variations: AA, AB, BA, and BB. A meaningful interaction effect would occur if, say, the AA combination outperforms the others by more than each test's individual effect would predict.

In practice, meaningful interaction effects are rare. More often, running tests in parallel simply increases variance without changing the overall results.

Novelty and Primacy Effects

Novelty and primacy effects are psychological phenomena that can influence the results of A/B testing. The novelty effect refers to the tendency of people to react positively to something new and different. In the context of A/B testing, a new design or feature may initially perform better than an existing design simply because it is new and novel. However, over time, the novelty effect may wear off and the performance of the new design may decrease.

The primacy effect refers to the tendency of people to remember and give more weight to information that they encounter first. With A/B testing, this can manifest as an initial reduction in the improvement for metrics as users prefer the original treatment of the product.

One way to mitigate the effects of novelty is to run tests over a longer period of time to allow for the novelty effect to wear off. Another approach is to stagger the rollout of a new design or feature to gradually introduce it to users and avoid a sudden and overwhelming change.

To account for the primacy effect, you can target or segment an experiment to just new users to ensure that they won’t be influenced by how things used to work. This can help ensure that the results of the test are truly reflective of user behavior and preferences, rather than the order in which designs were presented.